|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

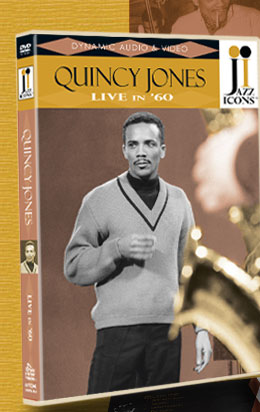

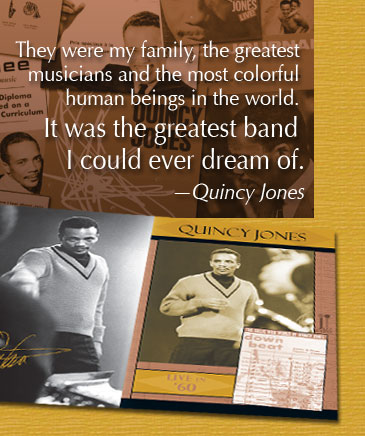

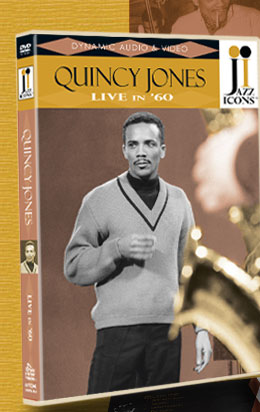

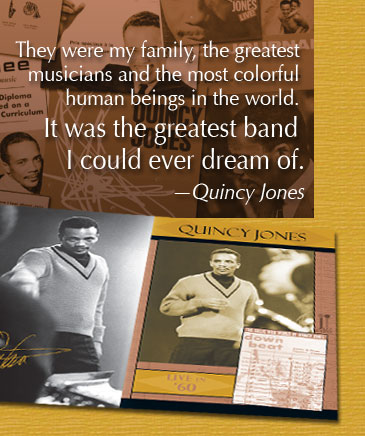

Jazz Icons: Quincy Jones spotlights a young “Q” conducting his “dream band”—an 18-piece orchestra of world-renowned players such as Clark Terry, Phil Woods, Sahib Shihab, Budd Johnson and Benny Bailey. This 80-minute program, featuring 17 songs, is one of the finest examples of big band jazz ever to be captured on film. Shot in Switzerland and Belgium in 1960, these two concerts are the only known visual documents of this legendary tour—an important lost chapter in an illustrious career which has spanned six decades. |

|

|

|

|

Conductor: Quincy Jones Alto Sax: Porter Kilbert, Phil Woods Tenor Sax: Budd Johnson, Jerome Richardson Baritone Sax: Sahib Shihab Piccolo: Jerome Richardson Trumpet: Benny Bailey, Leonard Johnson, Floyd Standifer, Clark Terry Trombone: Jimmy Cleveland, Quentin Jackson, Melba Liston, Ake Persson French Horn: Julius Watkins Guitar and Flute: Les Spann Piano: Patti Bown Bass: Buddy Catlett Drums: Joe Harris |

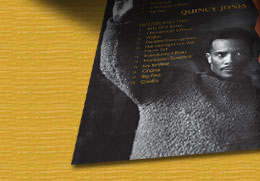

Birth Of A Band Moanin’ Lester Leaps In The Gypsy Tickle Toe Everybody’s Blues Big Red |

|

|

|

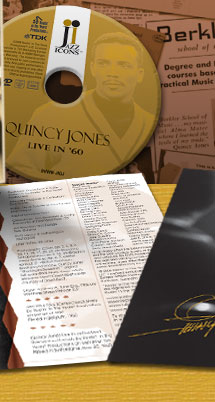

Conductor: Quincy Jones Alto Sax: Porter Kilbert, Phil Woods Tenor Sax, Piccolo & Flute: Jerome Richardson Baritone Sax: Sahib Shihab Trumpet & Flugelhorn: Benny Bailey, Roger Guerin, Leonard Johnson, Floyd Standifer Trombone: Jimmy Cleveland, Quentin Jackson, Melba Liston, Ake Persson French Horn: Julius Watkins Guitar and Flute: Les Spann Piano: Patti Bown Bass: Buddy Catlett Drums: Joe Harris |

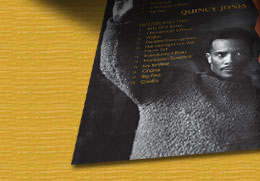

Birth Of A Band I Remember Clifford Walkin’ Parisian Thoroughfare The Midnight Sun Will Never Set Everybody’s Blues Stockholm Sweetnin’ My Reverie Ghana Big Red |

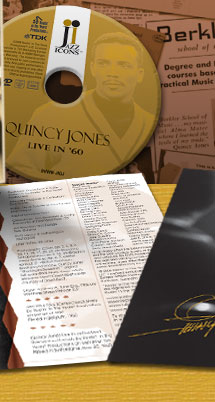

24-page booklet 1959 Jazz Review article written by Quincy Jones Afterword by Buddy Catlett Liner notes by Ira Gitler Cover photo by Susanne Schapowalow Booklet photos by Susanne Schapowalow, Elton Robinson Free And Easy rehearsal photo collage Memorabilia collage Total time: 80 minutes |

|

|

Excerpt from 1959 Jazz Review article by Quincy Jones: When I came back last November after 19 months in Europe, I decided to try to form a band. I’d seen signs that indicated—to me, anyway—that this is the time. I soon discovered that the amount of planning required was more than most writers on the subject—and most people asking what’s happened to the bands—realize. First, some of the signs. In Europe, there’s unusually large interest in big bands, and with the way transportation is developing, Europe will be a much more important part of any band’s itinerary in the years to come. By 1964, a band should be doing one-nighters to England or Germany with the same regularity as it goes to Pittsburgh. I think new bands will find they’ll be able to play more music in Europe than here. A key reason for wanting a band—and I know this feeling is shared by many musicians—was the constant discouragement and frustration of assembling a superior group of musicians for recording, of having them right there, and knowing what could happen if they could stay together for a month. First, I had to realize that I couldn’t get the good musicians I wanted unless I had enough work guarantees before I went out to assure them at least a few months. Finding musicians who’ll travel at all was one problem. Finding musicians who had had big band experience—in a period when there was practically nowhere for them to get it—was another. I also had to have musicians who were men as well as creative. Oddly enough, the two elements don’t often seem to go together. My men had to have good conception—not a studio approach—but they also had to be straight guys. One man with a dissonant personality can ruin a section, no matter how skilled a musician he is. And no junkies. They mess-up in every way. Their attitude runs through everything they do on and off the stand. They’re late to gigs, careless in appearance, and they goof musically. It’s hard enough to get a big band going without them on hand. As of this writing, I haven’t the full personnel set yet. Some sent in tapes. Musicians I knew recommended others. And I’d kept my ears open during all the time I’d spent on the road. It looks like the pianist will be Patti Bown. She, like Melba Liston in the trombone section, is a fine musician, not just a good girl musician. I’m against using women for novelty effect. I’ve known Patti since we were both about 12, when her mother wouldn’t let her play jazz. ... Sample Liner Notes by Ira Gitler: Quincy Jones was born in Chicago on March 14, 1933. By the time he had reached his formative years he was old enough to have soaked up the sounds of the Swing Era, but still young enough to be entranced by the evolution of bebop. For someone choosing to take up music as his profession, this was a golden era. When Jones was 10, his father, Quincy Delight Jones Sr., took the family west to Bremerton, Washington, near Seattle. His interest in music emerged, and he tried many instruments in the school band before settling on the trumpet at age 14. The following year he met Clark Terry who was in town with Count Basie. Terry had already mentored a young Miles Davis in St. Louis in the ’40s. Quincy told me, “Clark showed me how I should place the mouthpiece on my lips.” During this period, Quincy began a friendship with another teenager, three years his elder—singer and pianist Ray Charles. The two formed their own group and also played locally in the Bumps Blackwell band. In 1951 Jones won a scholarship to Boston’s Schillinger House (which later became the Berklee College of Music) and studied there until he joined Lionel Hampton’s orchestra in1952. .... “Birth of a Band” brings together Budd Johnson and Jerome Richardson (a versatile reedman who later played lead alto—and occasionally lead soprano—in the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis band.) The two each make opening statements before they engage in a tenor “battle,” a tradition set in the big band era. A short Bown solo leads back to the biting ensemble with Harris, as usual in command from behind his spare set. Harris, part of the great drumming lineage of Pittsburgh (Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey), helped power the Dizzy Gillespie band of 1946-48. “Moanin’,” the blues that pianist Bobby Timmons wrote when he was with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, is arranged by Quincy and features the fluent flugelhorn of the spirited Clark Terry, who has descended from up in the trumpets’ aerie to play at the bottom of the steps. “Lester Leaps In” was conceived by tenor saxophone great Lester Young, known as Prez, when he was in Count Basie’s orchestra and recorded by him with a Basie combo in 1939. I suspect this is a Budd Johnson chart. After Bown, a former child prodigy, sets the pace with a deft solo and Les Spann’s guitar begins the theme statement, Johnson and Richardson step up to play the first chorus of Prez’s original recorded solo. Then Johnson blazes away by himself, with added impetus through the use of stop-time. Piccolo (Richardson) and flute (Spann) exchanges lighten the sonic environment but not the groove. Spann had already revealed his multi-talents in Dizzy Gillespie’s quintet before joining Jones. The tempo slows for a Woods feature on “The Gypsy,” a song written by Billy Reid that was a hit in the ’40s. It was recorded by Charlie Parker in what is usually referred to as the “Lover Man” session (Hollywood, July 29, 1946). After listening to Woods’ version of “The Gypsy,” it felt to me as if he was playing this one for Bird. In places it seemed as if he was channeling him, especially leading up to and including the quote of “Dearly Beloved,” one of Bird’s favorite interpolations. In any event, it is an extremely moving solo and some close-ups of Woods’ face magnify the depth of the mood he creates. In one segment, four flugelhorns are part of the background and at the finish it’s all muted trumpets. On Ernie Wilkins’ “Everybody’s Blues” (also called “The Phantom’s Blues,” in honor of Julius Watkins), Terry joins Bailey in the wa-wa department, and the trombone solo is played by the soulful Melba Liston. Watkins’ French horn solo is subtle yet pungent. All words and artwork on this page ©Reelin' In The Years Productions. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

| |

Site contents ©Copyright 2006 Reelin' In The Years Productions

Site designed by Tom Gulotta